The Song

Of The Earth

The Song

Of The Earth

Dialogue of the Diverse

Dialogue of the Diverse

A Concert Project in Europe and Asia

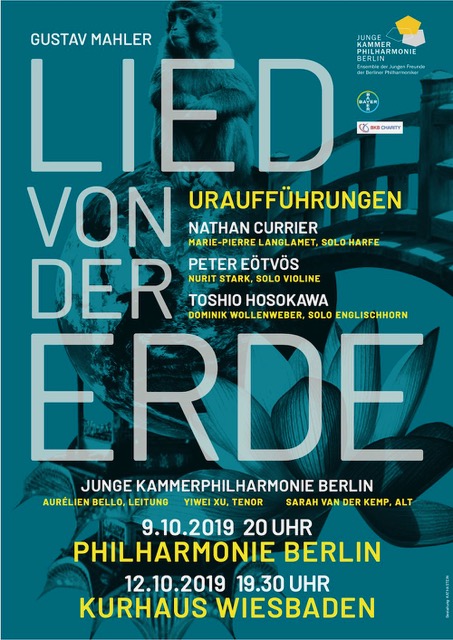

with three World Premieres

The Project

“For me though, the Symphony means using all available technical means to construct a world”

Gustav Mahler

Dialogue of the Diverse

Gustav Mahler’s Song of the Earth, a work about Life and Death, Youth and Old Age, Day and Night, combines western composition with an unfamiliar, far-eastern soundworld. We have adopted the Mahlerian concept Dialogue of the Diverse as the central focus of the concert project. The programme planning principles are unique, being inspired by the twin all-encompassing perspectives woven by Mahler throughout his Song of the Earth, right down to the structural level. As well as the German-Chinese ensemble which will play Mahler’s richly scored orchestral work in the Second Half, the First Half of the concert featured several world premieres performed by solo instrumentalists – each of which are written specifically for the project, making reference to Mahler’s work, both in content and compositional process. We have been especially fortunate in securing top-class soloists (Berlin Philharmonics) and composers from Japan, Hungary, Israel, Germany, France and the USA. They are undertaking the challenge of interpreting Mahler’s messages anew, through the means of solo music. Unfortunately, the concerts in China had to be postponed due to the pandemic. The project was conceived around an initial concert series, leaving other possibilities open - a second series is at the planning stage.

While Mahler sings in Symphony VIII “of a Thousand” (1906), of the enlightenment and liberation of man through sacred and secular love, in The Song of the Earth (1908), he “constructs” a new world. The composer himself designated the 8th Symphony as “the Greatest”, but The Song of the Earth as “the Most Personal”, work that he had created. It is not quite clear whether it was personal strokes of Fate – the early death of Mahler’s daughter or his own severe cardiac diagnosis and subsequent resignation from his position at the Wiener Staatsoper – or perhaps the discovery of Hans Bethge’s new versions of the ancient Chinese poetry, that gave the strongest impetus to compose The Song of the Earth. But what is clear is that through this work, Mahler unveils a new realm of reflection – integrating the lyricism, philosophy and compositional forms of an oriental and unfamiliar culture.

Just as Taoist philosophy reveals Creation as a binary force, given forth as Yin and Yang, Mahler builds The Song of the Earth out of self-generating, opposing and resolving contrasts and polarities. Each song reflects this through fundamental messages. They deal with issues such as mortality & eternity, life & the ever-after, night & day, youth & old age, solitude & companionship, the eternal Masculine & the eternal Feminine.

Mahler‘s creation establishes a meeting and connection with a cultural “Other”. Breaking the boundaries of our own cultural experience.

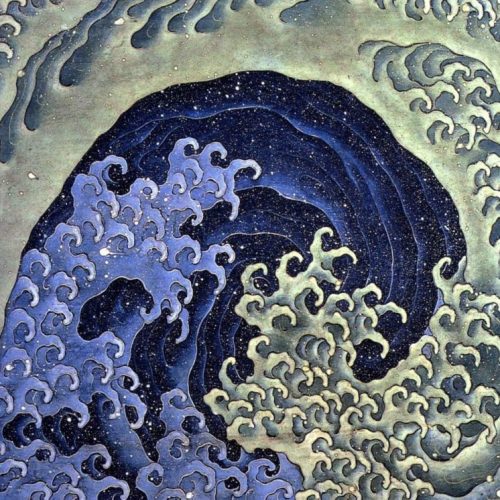

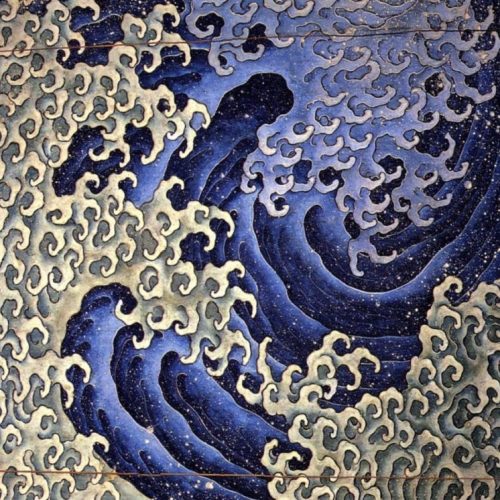

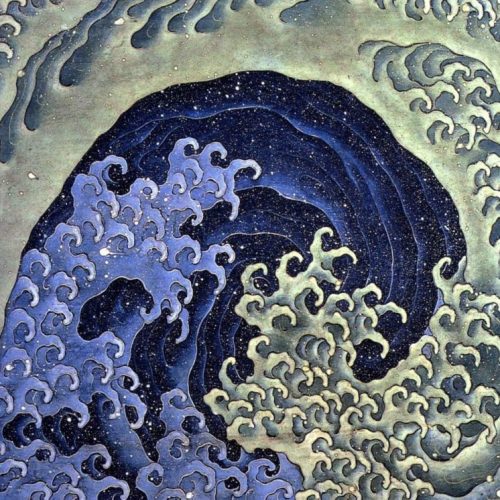

This can be seen particularly clearly in the song Von der Jugend (On Youth): a group of young friends are enjoying themselves in a pavilion standing in the middle of a pond (“inmitten eines Teiches”). A bridge is arching over towards them. The reflection of this scene in the water below turns everything on its head (“al- les auf dem Kopfe stehend”). Through such simple but evocative concepts, the poet Li Bai resists any tendency to make his subjective feelings explicit: whereas Mahler handles the text with the subjectivity characteristic of Romanticism. While he treats the first part of the song exotically, he inserts two further verses to the reflection scene, which in turn he develops musically with familiar colors from the Viennese tone palette. His portrayal of a youthful society in their pavilion evokes an idea of the composer’s own fantasies of a never-experienced, but longed-for idea of Youth.

Song-text: On Youth

Hans Bethge / Gustav Mahler

After the poetry of Li Bai

In the middle of the little pond

stands a pavilion of green

and white porcelain.

Like the back of a tiger

a jade bridge arches

over to the pavilion.

Friends sit in the little house

well-dressed, drinking, chatting.

Some writing verses.

Their silk sleeves glide

backwards, their silk caps

perch gaily at the napes of their necks.

On the small pond’s still

Surface, everything appears

curious in mirror image.

Everything standing on its head

And white porcelain.

The bridge like a half-moon,

Its arch upside-down. Friends,

Well-dressed, drink, chat.

„Was it a vision, or a waking dream; Fled is that music: – do I wake or sleep?“

(War es eine Vision oder ein wachender Traum? Geflohen ist jene Musik: – bin ich wach oder schlafe ich?)

aus: Ode an eine Nachtigall von John Keats

Contemporary Songs of the Earth for solo instruments

The concept of polar opposition, as already explored in a thematic context, also penetrates the formal structure of the work.In the final song Der Abschied (The Farewell) – at the moment of crossing from the living to the other side – all power is drained from the music. There are no tangible tempi, melodies lose clarity of contour, and the singer repeats the word “ewig” (enternally) on a descending two- note motif at ever-greater time-intervals until the music finally fades completely. All familiar signs of the passing, and onward-march, of the time have dissapeared from the music in the evocation of the “eternal distant glow”, a new reality existing beyond time. The listener has the sense that with the ending of the music, they are actually listening to the particular silence of this new reality.

Which aspects of this arena of confrontation between life and death inspire composers today? What does mortality mean to them, and what visions do they conjure up to depict the afterlife or eternity? Can a dual global perspective convince today? What musical solutions can the composers of today bring to the perspective of a single musician without words? Which subjects will inspire musicians, who have often played in The Song Of The Earth with a world-class orchestra, to great solo performance? How would their own Song of the Earth sound?

Beyond this, it is specifically through the new works’ soloistic nature that a radical new light is shone on one significant theme from The Song of The Earth: Solitude. Mahler occupies himself particularly with this theme in the second song Der Einsame im Herbst (The Loner in Autumn) the protagonist rejects the pressures of society in favour of a hermit-like existence amongst na- ture, and in the last song Der Abschied (The Farewell) takes this further into his permanent farwell (“Ich suche Ruh für mein einsam Herz.” - “I seek the repose of my solitary heart”) that. Solitude can also be said to correspond with Mahler‘s more personal reflections at the time of composition. In two letters of 1908 he writes to his friend and colleague Bruno Walter: “Here in my solitude*, where I am much more inwardly alert, I have a clearer sense of everything that is not psychologically healthy...” “But to come to terms with myself and be con- scious of everything that I am; I was only able to experience that through solitude... If I am again to trace the path to my Self, I must once again hand myself over to the trials of solitude.” [*on summer holiday in Toblach]

Sarah van der Kemp

The Project

“For me though, the Symphony means using all available technical means to construct a world”

Gustav Mahler

Dialogue of the Diverse

Mahlers Song of the Earth, ein Werk über Leben und Tod, Jugend und Alter, Tag und Nacht, verbindet abendländisches Komponieren mit einer fremdartigen fernöstlichen Klang-welt. Dialog des Unterschiedlichen – dieses Mahlersche Thema bildet den Mittelpunkt des Konzertprojekts. Mahlers Song of the Earth werden 3 Kompo-sitionen für Soloinstrumente gegenübergestellt – Kompositionen, die eigens für das Projekt geschrieben wurden und inhaltlich wie kompositorisch auf Mahlers Werk Bezug nehmen. Im ersten Teil die zeitge-nössischen Solostücke von und für erfahrene Profimusiker und Komponisten im zweiten Teil Mahlers Fin de Siècle-Werk für 100 Musiker, interpretiert von angehenden jungen Musikern: Die polare Struktur des Lieds von der Erde soll bis in die Programmgestaltung hinein spürbar werden. Eine Tournee durch Asien und Europa liegt nahe. Leider mussten die Konzerte in China wegen der Pandemie verschoben werden.

Das gesamte Projekt ist als Konzertserie in offenem Prozess angelegt; eine zweite Staffel steht in Planung.

While Mahler sings in Symphony VIII “of a Thousand” (1906), of the enlightenment and liberation of man through sacred and secular love, in The Song of the Earth (1908), he “constructs” a new world. The composer himself designated the 8th Symphony as “the Greatest”, but The Song of the Earth as “the Most Personal”, work that he had created. It is not quite clear whether it was personal strokes of Fate – the early death of Mahler’s daughter or his own severe cardiac diagnosis and subsequent resignation from his position at the Wiener Staatsoper – or perhaps the discovery of Hans Bethge’s new versions of the ancient Chinese poetry, that gave the strongest impetus to compose The Song of the Earth. But what is clear is that through this work, Mahler unveils a new realm of reflection – integrating the lyricism, philosophy and compositional forms of an oriental and unfamiliar culture.

Just as Taoist philosophy reveals Creation as a binary force, given forth as Yin and Yang, Mahler builds The Song of the Earth out of self-generating, opposing and resolving contrasts and polarities. Each song reflects this through fundamental messages. They deal with issues such as mortality & eternity, life & the ever-after, night & day, youth & old age, solitude & companionship, the eternal Masculine & the eternal Feminine.

Mahler‘s creation establishes a meeting and connection with a cultural “Other”. Breaking the boundaries of our own cultural experience.

This can be seen particularly clearly in the song Von der Jugend (On Youth): a group of young friends are enjoying themselves in a pavilion standing in the middle of a pond (“inmitten eines Teiches”). A bridge is arching over towards them. The reflection of this scene in the water below turns everything on its head (“al- les auf dem Kopfe stehend”). Through such simple but evocative concepts, the poet Li Bai resists any tendency to make his subjective feelings explicit: whereas Mahler handles the text with the subjectivity characteristic of Romanticism. While he treats the first part of the song exotically, he inserts two further verses to the reflection scene, which in turn he develops musically with familiar colors from the Viennese tone palette. His portrayal of a youthful society in their pavilion evokes an idea of the composer’s own fantasies of a never-experienced, but longed-for idea of Youth.

Song-text: On Youth

Hans Bethge / Gustav Mahler

After the poetry of Li Bai

In the middle of the little pond

stands a pavilion of green

and white porcelain.

Like the back of a tiger

a jade bridge arches

over to the pavilion.

Friends sit in the little house

well-dressed, drinking, chatting.

Some writing verses.

Their silk sleeves glide

backwards, their silk caps

perch gaily at the napes of their necks.

On the small pond’s still

Surface, everything appears

curious in mirror image.

Everything standing on its head

And white porcelain.

The bridge like a half-moon,

Its arch upside-down. Friends,

Well-dressed, drink, chat.

„Was it a vision, or a waking dream; Fled is that music: – do I wake or sleep?“

(War es eine Vision oder ein wachender Traum? Geflohen ist jene Musik: – bin ich wach oder schlafe ich?)

aus: Ode an eine Nachtigall von John Keats

Lieder von der Erde

für Soloinstrumente

The concept of polar opposition, as already explored in a thematic context, also penetrates the formal structure of the work.In the final song Der Abschied (The Farewell) – at the moment of crossing from the living to the other side – all power is drained from the music. There are no tangible tempi, melodies lose clarity of contour, and the singer repeats the word “ewig” (enternally) on a descending two- note motif at ever-greater time-intervals until the music finally fades completely. All familiar signs of the passing, and onward-march, of the time have dissapeared from the music in the evocation of the “eternal distant glow”, a new reality existing beyond time. The listener has the sense that with the ending of the music, they are actually listening to the particular silence of this new reality.

Which aspects of this arena of confrontation between life and death inspire composers today? What does mortality mean to them, and what visions do they conjure up to depict the afterlife or eternity? Can a dual global perspective convince today? What musical solutions can the composers of today bring to the perspective of a single musician without words? Which subjects will inspire musicians, who have often played in The Song Of The Earth with a world-class orchestra, to great solo performance? How would their own Song of the Earth sound?

Beyond this, it is specifically through the new works’ soloistic nature that a radical new light is shone on one significant theme from The Song of The Earth: Solitude. Mahler occupies himself particularly with this theme in the second song Der Einsame im Herbst (The Loner in Autumn) the protagonist rejects the pressures of society in favour of a hermit-like existence amongst na- ture, and in the last song Der Abschied (The Farewell) takes this further into his permanent farwell (“Ich suche Ruh für mein einsam Herz.” - “I seek the repose of my solitary heart”) that. Solitude can also be said to correspond with Mahler‘s more personal reflections at the time of composition. In two letters of 1908 he writes to his friend and colleague Bruno Walter: “Here in my solitude*, where I am much more inwardly alert, I have a clearer sense of everything that is not psychologically healthy...” “But to come to terms with myself and be con- scious of everything that I am; I was only able to experience that through solitude... If I am again to trace the path to my Self, I must once again hand myself over to the trials of solitude.” [*on summer holiday in Toblach]

Sarah van der Kemp

Patronage

Under the Patronage of State Minister for Culture and Media

Frau Prof. Monika Grütters MdB

World Premieres

All world premieres are commissioned by the Junge Kammerphilharmonie Berlin as part of the concert series The Song Of The Earth - Dialogue of Diverses based on an idea by Sarah van der Kemp.

I was then a man dreaming I was a butterfly,

or whether I am now a butterfly, dreaming I am a man.«

Zhuangzi, chinesischer Philosoph (365 – 290 v. Chr.)

Toshio Hosokawa:

Still ist mein Herz

und harret seiner Stunde

Dominik Wollenweber,

Englishhorn Solo

Toshio Hosokawa:

For me, Das Lied von der Erde is one of the most important works of western music. It takes on the text of a Chinese poet that was translated into German, and through this, Mahler’s world of eastern music is expressed. In the final movement, ‘Abschied’, the people crossing the borderline to and fro between this world and the other, are deeply expressed by the music. In ancient Chinese philosophy, the borderlines between this world and the other, as well as between dream and reality, are ambiguous and chaotic. From this eastern world view, I have considered music to be the instrument that connects this world and the other, and have carried out my compositional activities on the understanding that musicians are shamans that connect these two worlds. In this solo piece, a characteristic motif of the oboe in Abschied is often used. My music is a sonic calligraphy of time and space, and the english horn was the perfect instrument to express my calligraphic line and frequent use of portamentos and appoggiaturas. The title derives from the text of Abschied.

Nathan Currier:

Vom Leid der Erde

Sonata for harp

1. Der Affenmensch heult nach seinem Windgott

2. Gaia’s Abschied von ihrer irdischen Harfe

Marie-Pierre Langlamet,

harp solo

Nathan Currier:

It is hard for me to contemplate Das Lied von der Erde today without some reference to the obvious: Mahler initially wanted to call his work Das Lied vom Jammer der Erde, and today’s ‘Jammer der Erde’ has become a primary fact of contemporary life. As a teenager Mahler’s music spoke to me with some special urgency, and it’s shocking to think how much of our destruction has been wrought since then – quickly checking a NOAA CO2 graph, I see that almost two thirds of civilization’s whole increase in CO2 since industrialization’s start has come. Now I understand that urgency, which I still feel, differently. Today I see Mahler’s largest works as personal expressions of Haeckelian Monism, which I see as holding important seeds for the future. Haeckel, who coined the term ecology, also helped to initiate the idea of endosymbiosis, being perhaps the first to notice that chloroplasts (Haeckel also named and was the discoverer of the plastids) seemed like cyanobacteria trapped inside plant cells. Understanding our planet’s self-regulatory mechanisms will be key, and the symbiogenetic basis of evolutionary novelty will likely be shown to be at the core of such mechanisms. In other words, both as metaphor and as guide to action, the Haeckelian thinking Mahler confronted is still entirely contemporary.

Vom Leid der Erde takes three common species I live around (on a horse farm), and introduces their voices into classical music in a sequential order, equating the seasonal passage there from winter to spring. Almost like the French horn’s quality of holding together the sections of an orchestra, the Aeolian harp plays a key role in binding together the components, and in mediating the inherent need for technology to dialogue with Nature in this way. The Aeolian harp is the sole instrument that plays only harmonics, and the complexity of its effects stems from the Karman vortex street effect of the wind. I use just three tunings: 1. what I like to call Mahler’s ‘Nature chord’, eerie, as in the first movement of his 3rd , the minor-major seventh chord, meant to depict the beginnings of life (Mahler wrote to Nathalie Bauer-Lechner, while composing it, that Nature was fundamentally ‘eerie’), 2. the dissonant 9-note chord that climaxes the first movement of the incomplete 10th, and 3. a purely pentatonic collection. Great horned owls were nesting on the farm this past winter, but unfortunately I hadn’t started my piece and didn’t record them, (and so had to use external sources) but the red-wing blackbirds and American toads I recorded as they arrived, both on the farm and the surrounding fields."

Peter Eötvös:

Adventures of the

Dominant Seventh Chord

Nurit Stark,

Violin solo

Peter Eötvös:

There is scarcely a chord that typifies western classical music more than the dominant seventh. It is typical, first and foremost, because it occurs so frequently; and this is because it has a special function: to prepare the ground for a cadence. On hearing this chord, you are safe in the knowledge that the musical phrase is to be completed. Or not, as the case may be! Perhaps there will be a so-called Interrupted Cadence, misleading the listener with a knowing smile. But in Adventures of the Dominant Seventh Chord my intention was to mislead no-one; rather perhaps to catch out the trusty old dominant seventh whenever we use it to undertake a surprising leap, crossing over from Western to Eastern European culture. The dominant seventh chord prepares the way for a calm and orderly point of closure; but what actually follows in this piece is something quite different: dance music in the style cultivated by the folk musicians of Transylvania. My piece sets up a confrontation between two musical cultures, but I do not think that they are in conflict with one another. It is simply that they are separated by a virtual, and in this case fully audible, border; they are just different. Western European music is composed music, written down for subsequent interpretation by the performer. By contrast, most Eastern European folk musicians are unable to read music; instead, they learn by ear, soon making the music "their own." In Transylvanian dance music, it is the violin that takes the leading role, playing the melody to which the other instruments supply rhythmic and harmonic accompaniment. In Adventures of the Dominant Seventh Chord, fast and slow dances alternate, with the dominant seventh chord frequently appearing between them - each time in a different guise. If the chord were to catch sight of himself in the mirror, he would barely recognise himself, so drastic are the changes wrought through expansion or contraction of his intervals - a real adventure of endless surprises.

World Premieres

All world premieres are commissioned by the Junge Kammerphilharmonie Berlin as part of the concert series The Song Of The Earth - Dialogue of Diverses based on an idea by Sarah van der Kemp.

1. Solo Englischhorn

»I was then a man dreaming I was a butterfly, or whether I am now a butterfly, dreaming I am a man.«

Zhuangzi, chinesischer Philosoph (365 – 290 v. Chr.)

Toshio Hosokawa:

Still ist mein Herz

und harret seiner Stunde

Dominik Wollenweber,

Englishhorn Solo

Toshio Hosokawa:

Das Lied von der Erde ist für mich eines der wichtigsten Werke der abendländischen Musik. Mahler verwendet Nachdichtungen chinesischer Texte und komponiert so seine Sicht auf die östliche Musik. Im Schlusssatz „Der Abschied“ findet der Weg des Menschen vom Diesseits ins Jenseits tiefen Ausdruck.

In der altchinesischen Philosophie sind die Grenzen zwischen Diesseits und Jenseits, Traum und Wirklichkeit keineswegs klar gezogen. Aus dieser östlichen Weltsicht heraus betrachte ich die Musik als ein Instrument, beide Welten miteinander zu verbinden. Tatsächlich beruht meine kompositorische Arbeit auf der Überzeugung, dass Musiker Schamanen sind.

In dieser Solokomposition verwende ich häufig ein charakteristisches Oboenmotiv aus dem Lied „Der Abschied“. Meine Musik ist eine akustische kalligraphische Linie von Zeit und Raum, und das Englischhorn das perfekte Instrument, um diese kalligraphischen Linien und die häufig verwendeten Portamenti und Appoggiaturen ausdrücken. Der Titel ist ein Zitat des Liedes "Der Abschied".

2. Solo Harfe

Nathan Currier:

Vom Leid der Erde

Sonata for harp

1. Der Affenmensch heult nach seinem Windgott

2. Gaia’s Abschied von ihrer irdischen Harfe

Marie-Pierre Langlamet,

harp solo

Nathan Currier:

Es ist schwierig für mich, über Das Lied von der Erde nachzudenken, ohne dabei auf etwas Wesentliches hinzuweisen: Mahler hatte ursprünglich vor, sein Werk "Das Lied vom Jammer der Erde" zu nennen. Der heutige „Jammer der Erde“ – die Zerstörung des Planeten durch den Menschen – ist zu einer primären Bedrohung unserer Zeit geworden.

Bereits als Jugendlicher hörte ich in Mahlers Musik eine besondere Dringlichkeit, und es schockiert mich, in welchem großen Ausmaß die Zerstörung seit meiner Jugend fortgeschritten ist: Die CO2-Konzentration stieg in diesem Zeitraum um eine Menge an, die zwei Drittel des Gesamtanstiegs seit Beginn der Industrialisierung entspricht (US-Klimabehörde NOAA).

Heute verstehe ich diese Dringlichkeit anders. Ich sehe Mahlers größte Werke als persönlichen Ausdruck eines Monismus nach dem Mediziner und Philosophen Ernst Haeckel (1834-1919), der die Natur pantheistisch, als Einheit von Materie und Geist, verstand; Ansätze, die für uns überlebensnotwendig sind.

Haeckels prägte den Begriff Ökologie und legte den Grundstein für unser Verständnis von symbiotioschen Lebensgemeinschaften zwischen Bakterien und Zellen.

Es ist von entscheidender Bedeutung, die Mechanismen der Selbstregulierung unseres Planeten zu verstehen, und die Rolle der Symbiose für evolutionäre Neuerungen wird dafür zentral sein – die haeckelsche Weltsicht, mit der Mahler vertraut war, ist heute noch aktuell.

Aus der Sicht von Mahlers Dritter Sinfonie der "Fröhlichen Wissenschaft" wird schnell klar: Haeckel verbreitete den Darwinismus in Deutschland und eben dies wurde zum Gegenstand von Mahlers Dritter Sinfonie. Aber der Anstoßpunkt für den Weltskandal – "Wir stammen vom Affen ab?" fehlt in diesem Werk. Denn Mahler stellte den Ursprung des Lebens, der Pflanzen und Tiere, der Menschheit und schließlich der Sphäre des menschlichen Geistes („Noosphäre“) und der menschlichen Liebe dar, ohne auf unsere unmittelbaren Ursprünge einzugehen.

Wenige Monate vor der Uraufführung der Dritten Sinfonie wurde Gustav Klimts Beethovenfries enthüllt, in dem Klimt Mahler als heroischen Ritter erscheint, der es mit dem schrecklichsten Sohn der Erdmutter Gaia, dem Giganten Typhon, aufnehmen muss, den Klimt brillant in einen riesigen Gorilla verwandelt. Im "Lied von der Erde" setzt Mahler den Affen an vorderste Front in Szene, wenn dieser im ersten Lied über Gräber der Menschen hinweg heult.

Vom Leid der Erde takes three common species I live around (on a horse farm), and introduces their voices into classical music in a sequential order, equating the seasonal passage there from winter to spring. Almost like the French horn’s quality of holding together the sections of an orchestra, the Aeolian harp plays a key role in binding together the components, and in mediating the inherent need for technology to dialogue with Nature in this way. The Aeolian harp is the sole instrument that plays only harmonics, and the complexity of its effects stems from the Karman vortex street effect of the wind. I use just three tunings: 1. what I like to call Mahler’s ‘Nature chord’, eerie, as in the first movement of his 3rd , the minor-major seventh chord, meant to depict the beginnings of life (Mahler wrote to Nathalie Bauer-Lechner, while composing it, that Nature was fundamentally ‘eerie’), 2. the dissonant 9-note chord that climaxes the first movement of the incomplete 10th, and 3. a purely pentatonic collection. Great horned owls were nesting on the farm this past winter, but unfortunately I hadn’t started my piece and didn’t record them, (and so had to use external sources) but the red-wing blackbirds and American toads I recorded as they arrived, both on the farm and the surrounding fields."

3. Solo Violine

Peter Eötvös:

Adventures of the

Dominant Seventh Chord

Nurit Stark,

Violin solo

Peter Eötvös:

In der abendländischen klassischen Musik gibt es kaum einen typischeren Akkord als den Dominantseptakkord. Typisch ist er, weil er häufig vorkommt. Und das liegt daran, dass er eine besondere Funktion besitzt: nämlich die, einen Abschluss vorzubereiten. Wenn man diesen Akkord hört, kann man sicher sein, dass die Phrase abgeschlossen wird. Oder eben noch nicht! Vielleicht folgt ein sogenannter Trugschluss, der den Zuhörer schmunzelnd irreführt?

In Adventures of the Dominant Seventh Chord wollte ich niemanden in die Irre führen, vielleicht nur die gute alte Dominantseptime dadurch überraschen, dass wir jedes Mal einen großen Sprung machen, wenn wir von der westeuro-päischen Kultur zur osteuropäischen übergehen. Der Dominantseptakkord bereitet einen ruhigen Abschluss vor, aber es folgt etwas ganz anderes: eine Tanzmusik in dem Stil, wie ihn die Volksmusiker in Transsylvanien zu spielen pflegen.

In meinem Stück werden zwei Musikkulturen gegenübergestellt, aber ich denke nicht, dass zwischen ihnen ein Konflikt besteht – bloß eine virtuelle, in diesem Fall gut hörbare Grenze. Sie sind eben unterschiedlich. Die westliche ist kom-poniert und notiert und wird von den Musikern interpretiert. Der östliche Volksmusiker dagegen kann meistens keine Noten lesen, er lernt nach dem Gehör und bald darauf ist es "seine Musik".

In der transsylvanischen Tanzmusik spielt der Geiger die Hauptrolle. Er spielt die Melodie, die anderen liefern rhythmische und harmonische Elemente dazu. In den Adventures of the Domi-nant Seventh Chord wechseln sich schnelle und langsame Tänze ab. Dazwischen erscheint ziemlich häufig der Dominantseptakkord – immer in veränderter Form. Wenn er in den Spiegel schauen würde, könnte er sich selbst kaum erkennen, denn seine Intervalle sind größer oder kleiner geworden: ständige Überraschung, ein richtiges Abenteuer.

The Program

First Half:

SONGS OF THE EARTH

FOR SOLO INSTRUMENTS

3 World Permieres

1. OBOE SOLO

Spell Song

2. ENGLISHHORN SOLO World Permiere

Still ist mein Herz und harret seiner Stunde

Composer: Toshio Hosokawa

Dominik Wollenweber, Oboe

+ Englishhorn

3. HARP SOLO World Permiere

Vom Leid der Erde

Sonata for harp

1. Der Affenmensch heult nach seinem Windgott

2. Gaia's Abschied von ihrer irdischen Harfe

Composer: Nathan Currier

Marie-Pierre Langlamet , harp

4. VIOLIN SOLO World Permiere

Adventures of the Dominant Seventh Chord

Composer: Peter Eötvös

Nurit Stark, violin

Second Half:

THE SONG OF THE EARTH

Composer: Gustav Mahler

Symphony for vocal and orchestra

1. Das Trinklied vom Jammer der Erde

2. Der Einsame im Herbst

3. Von der Jugend

4. Von der Schönheit

5. Der Trunkene im Frühling

6. Der Abschied

China Tour

Due to the corona pandemic, the planned tour to China in March 2020 was postponed indefinitely.

Due to the corona pandemic, the planned tour to China in March 2020 was postponed indefinitely.

"Projects like this make a significant contribution to international understanding, especially because it is a real co-production of German and Japanese musicians. The project is therefore very worthy of support."

Michelle Müntefering

Minister of State at the Federal Foreign Office

Impressions

Trailer

Berlin Philharmonic

October 10th, 2019

Radio Feature

A radio feature

from October 27th

Author: Julia Kaiser

Gallery

Rehearsals and concert

Berlin Philharmonic

Photos: Jakob Tillmann

Impressions

Trailer

Radio Feature

Author: Julia Kaiser

Gallery

Photos: Jakob Tillmann

About

Tenor

Yiwei Xu

About

Yiwei Xu

Tenor

Orchestra

Junge Kammerphilharmonie Berlin

+ Guests

Lectures of the Berlin Philharmonics

BESETZUNG FLÖTE Mia Schmidt, Leon Bruder, Stefanie Mutke, Elisabeth Hufnagel OBOE Dominik Wollenweber*, Lea Reib, Jian Kim KLARINETTE Ulrich Schuster, Fabian Hafner, Adrian Seeliger, Olga Zenker FAGOTT Katharina Buchwald, Gary Hirche, Antonia Brinkman HORN Sakura Koyama, Christiane Hultsch, Thomas Mittler, Midori Harada TROMPETE Lukas Bach, Robert Schmalz, Florian Oberließen POSAUNE Laurin Kapitzki TUBA Jannik Schmidt PAUKE Gerrit Bogdahn SCHLAGWERK Kaspar Querfurt, Irma Hei nig, Seongcheol Choi HARFE Marie-Pierre Langlamet* MANDOLINE Felix Herron CELESTA Pia Stüssel VIOLINE 1 Marlene Ito*, Lukas Abel, Liv Colell, Daniele Daude, Yuya Fukushima, Kana Himeno, Michaela Jacob, Johanna Jerye, Max Lewandowski, Emanuela Matei, Dorothea Schwerk, Benjamin Springborn, Patricia Stoehr, Sebastian von Streit, Jakob Wolansky, Connie Xu VIOLINE 2 Marisa Klemp, Clara Boeninger, Maria Borst, Constanze Busch, Marika Constant, Gabriela Diez, Kathrin Geisemeyer, Barbara Gerster, Peter Mittag, Madeleine Onwuzulike, Nurit Stark, Lilith Rogowski, Henrike Struck, Charlotte Wernicke VIOLA Tobias Opialla, Konrad Bucher, Felix Herron, Matthew Hunter*, Annemarie Kattner, Bianca Kaulich, François Lallemang, David Schroeren, Benjamin Spendrin VIOLONCELLO Johannes Zimmermann, Kai Chou, Björn Grünewälder, Andreas Herrmann, Gregor Kübler, Anna Lebowsky, Martin Löhr*, Julia Nothdurft, Theresa Schlagheck, Franziska Schulz, Kim Zietlow KONTRABASS Martin Krischer, Dominic Edgeley, Julius Deckel mann, Johannes Hanekamp, Ben Sahlmüller, Jonas Scholz, Timm Schulz, Gunars Upatnieks*.

*Mitglied der Berliner Philharmoniker

Contact

Orchestra

Orchestra Board:

Conductor